King Dollar

7 July 2022

Oh hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

Welcome back to We Study Markets. The S&P 500 closed up for the third day in a row yesterday 🎉.

In bear markets, it’s the small things that matter.

Today we’ll be discussing the dollar and its role in the global financial system, the Fed’s latest meeting, Warren Buffett’s tip to novice investors, and much more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Here we go!

In The News

⛽ Commodity sell-off highlights global recession concerns (FT)

Explained:

- A number of important commodities have hit lows recently, such as oil and wheat, which are now almost back to their price level prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And Copper, also called Dr. Copper by some for its ability to predict economic trends based on its price (since the metal is a key input throughout the economy) is now trading near an 18-month low. Rather than reflecting a sudden increase in supply, as the world desperately needs, these price declines more likely reflect shifting speculator sentiment anticipating reduced demand for these commodities. The primary reason demand would be dramatically reduced going forward, is well, because of an economic slowdown, or to use jargon, a recession.

What to know:

- While this provides some hope that inflation may cool off soon, a recession is not necessarily good news for equity investors. If we manage to avoid a recession (a recession would dramatically reduce global demand for energy and commodities), don’t expect this reprieve in lower commodity prices to last, as a moderate uplift in demand expectations would likely send prices much higher again. Commodity markets continue to remain very tight, and boosting supply, especially for oil, cannot happen overnight. We expect things to be quite volatile for the foreseeable future.

📈 Wall Street ends higher as investors absorb Fed minutes (Reuters)

Explained:

- The FOMC minutes were published yesterday detailing the Fed’s June 14-15 meeting. Fed officials have agreed to raise interest rates faster to levels that may dampen economic growth while hopefully curbing inflation. Another .75 point increase appears to be on the table for later in July. The major indexes ended modestly up after investors attempted to decipher future hints to the Fed’s stance on further interest rate increases. The minutes suggest that the Fed is viewing inflation as their primary concern which is no longer a “transitory” issue. They also indicated an acceptance that fighting inflation will lead to a much higher risk of a recession.

What to know:

- The Fed has stated its goal is to reduce inflation to roughly 2%. Interest rate hikes alone may prove unable to accomplish this as there

are several exogenous events, including the war in Ukraine and continued supply chain disruptions, that are beyond the Fed’s ability to control. With consumer prices running at an 8.6% rate, and GDP on pace to decline 2.1% in the second quarter, the Fed seems to be running out of tools to meet its dual mandate of price stability and maximum sustainable employment. For more on the Fed’s policies and what it may mean for your portfolio, check out our Bitcoin Fundamentals podcast episode 85 with Sven Henrich.

🤕 Venture capital feels the stock market’s pain (WSJ)

Explained:

- Rising interest rates aren’t just hurting equity markets. The effect is rippling throughout the entire financial system, and venture capital, which refers to a segment of the private equity industry that focuses on providing capital to start-ups and other small businesses, is particularly vulnerable. When interest rates on government bonds increase, investors can earn yields on these assets that are considerably safer than they would by investing in many of the unprofitable young companies so common in Silicon Valley. In other words, it’s harder to entice investors to provide funding for speculative companies in this environment. Deal-making declined from roughly $70 billion in the first quarter of this year to $47 billion in the second quarter.

What to know:

- With increasingly limited funding for companies in the venture capital space, expect there to be more bankruptcies and fewer IPOs in public markets. If you’re thinking of starting the “next big thing”, you may find that investors are a whole lot less generous than they were even just a few months ago.

Sponsored By

How do you make sure that you are investing with a “good” operator?

Dan Handford and his wife are currently invested in 54 different passive real estate syndications with 16 different operators in 10,000+ doors.

They use this exact list when deciding whether or not to invest with a particular group. Get access to the “7 Red Flags for Passive Real Estate Investing” to be confident in your next investment!

Deep Dive: King Dollar

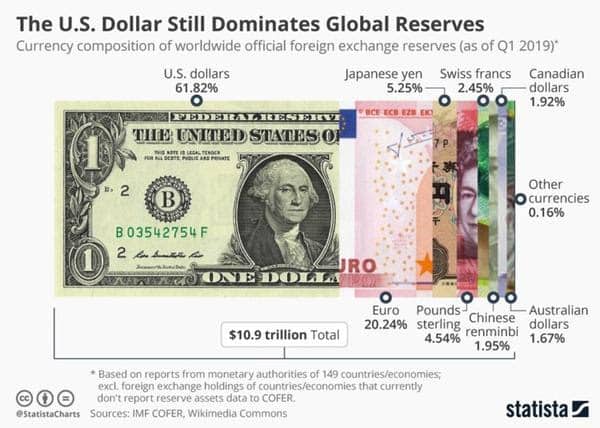

The world is deeply reliant on the U.S. dollar as a means for settling global trade and raising capital. While under the Bretton Woods System, which lasted from 1944–1971 and cemented the dollar’s role in global financing, many national currencies were pegged explicitly to the dollar, which was pegged to gold at a fixed exchange rate.

As the only major power that didn’t have its manufacturing base nearly entirely wiped out by the war, the U.S. was in quite a position of strength to dictate the new world order according to its own terms.

Outside of Europe (where the Euro acts as the reserve currency), the world relies overwhelmingly on using the dollar as a neutral settlement between two countries with differing currencies still to this day. The reality is that there are many, many complex effects of this engineered system, but the primary takeaway is that the world needs access to dollars.

The Bretton Woods System, however, broke in 1971 when the U.S. essentially defaulted on its debt by revoking the dollar’s redeemability into gold (interestingly enough, France actually sent an aircraft carrier to New York to try and collect the gold it was owed).

This means America didn’t have the gold to make good on its liabilities, and instead of explicitly defaulting, the world was ultimately pushed into a new paradigm of ‘fiat’ currencies following the failure of the Smithsonian Agreement.

Under the fiat system within which we currently operate, our money isn’t backed by specific exchange rates to real assets, but rather by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

Shifting back towards the world’s need to settle transactions in dollars given its role as the preeminent global reserve currency, which it has maintained since 1944 despite the collapse of Bretton Woods, this artificial demand for dollars is perpetuated, in part, by U.S. arrangements to provide military protection in exchange for countries denominating their exports in dollars (i.e the Saudi Arabian petrodollar system).

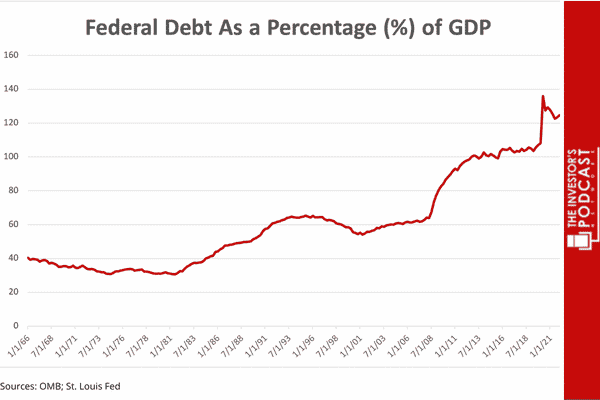

This dynamic has allowed the U.S. to run both balance of payment and fiscal deficits for nearly 50 years. Normally, when a country imports more than it exports, its savings should be drawn down, thus reducing its ability to pay down debts and deteriorating its currency’s value (who wants to hold the currency of a government that can’t pay its debts?).

With a weaker currency, the country’s exports become more competitive, since its goods are now cheaper for others to import. Increased foreign demand boosts exports relative to imports, fuels economic growth, and returns the economy to a more stable equilibrium.

Lyn Alden explains this well in discussing the global economy under the Bretton Woods System:

“Whenever a country began persistently importing more than it was exporting, it risked having gold flow out of the country and risked economic stagnation within the homeland. Ultimately, however, this state would usually be self-correcting because a recession would eventually devalue the currency, which would make their exports more competitive and imports more expensive, and thus re-align their export and import balance.”

The idea is the same here for fiscal deficits. When governments increasingly fund their deficits with borrowed money, the currency should depreciate in value relatively as the country’s solvency becomes more questionable.

If there is an unsustainable amount of government spending, the country’s credit ratings will be downgraded, thus raising the cost of issuing new debt, which in theory would disincentivize excess spending going forward due to the large interest costs, particularly if it’s denominated in a currency they cannot print.

However, America’s debts are, uniquely, entirely in its own currency.

With its ‘exorbitant privilege’, as American economist Barry Eichengreen summarized, “It costs only a few cents for the (U.S.) Bureau of Engraving and Printing to produce a $100 bill, but other countries had to pony up $100 of actual goods in order to obtain one.”

So what’s the issue?

All of this to say, the world changed profoundly in 1971 when the United States found a new way to extend its global power by shedding its gold standard.

In the decades since, Americans have benefited greatly as consumers given the country’s national ability to persistently consume beyond its means. This is because the dollar, in some sense, cannot meaningfully depreciate relative to other fiat currencies given the synthetic demand for dollars as the global reserve currency, especially now that it’s unhindered by any connection to gold.

To think of it another way, if the U.S. were not the global reserve currency, it would risk currency devaluation each year in response to its current account and fiscal deficits. Because the devaluation mechanism is perverted by the dollar’s reserve status, despite America’s underlying financial fundamentals, the country has effectively hollowed out its middle-class and blue-collar industries because its exports cannot be competitively priced.

The takeaway?

For the rest of the world, reliance on the U.S dollar as a means for storing wealth, settling international trade, and raising capital, is at best a periodic inconvenience, and at worst, ensnares them in the complex web of American geopolitics, for no reserve currency issued by a single sovereign can fully divorce itself from the political interests of said government.

The U.S. has sanctioned countries like Iran and Russia by seeking to reduce their access to international bank accounts and investment through their relationships with U.S counterparts and the Federal Reserve. It’s become clear to the rest of the world then that their financial independence is largely tied to the political whims of the powers at be in Washington.

Objectively, this monopoly system is not one that many countries likely enjoy participating in, but given the dollar’s critical role in the global economy, many are left asking what’s the alternative?

For more on the dollar and the history of money, check out Stig Brodersen’s interview with Lyn Alden on We Study Billionaires.

Quote of the Day

Meaning

Many like the idea of investing but are unwilling to do the work necessary to pick stocks, so passive strategies are a perfect compromise.

By not putting all your eggs in one basket, you’ll be more likely to navigate tumultuous and uncertain times effectively, especially when there are headlines on the news flashing emergency warnings for the markets.

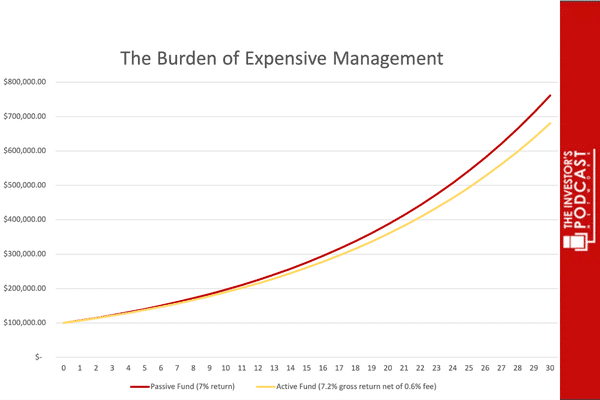

Betting on the market broadly via index funds has been a much better choice than pouring money into funds that actively try to pick stocks. On average, half of these money managers will perform worse than the market benchmark, and much of the rest will charge fees so high that you still end up doing worse than a simple index fund.

More on index investing below👇

The burden of expensive management

Warren Buffett famously bet that Wall Street’s finest couldn’t beat a simple S&P 500 index fund over a several-year period.

Surely, this is a task that sophisticated hedge funders could achieve, right?

Surprisingly, no.

Protégé Partners, LLC entered into a $1 million charitable wager with Buffett, selecting five hedge funds that from 2008 to 2017 they expected to perform better than the market benchmark. Even with the crash from the Great Recession, the S&P 500 index fund dominated with returns of 85.4% versus the 22% hedge fund average.

Despite skilled management, robust trading systems, and advanced algorithms, simply ‘buying the market’ was a much better decision for you than these hedge funds.

Yet, Wall Street loves to package investment products in shiny wrapping with fancy language to coax you into paying more for something you may not need.

If management fees are greater than 0.5%, you should be skeptical, and for most investors, any fund with fees greater than 0.75% should be ruled out.

The amount you pay in fees is solely up to you, so don’t get tripped up by a product that sounds sophisticated, but in reality, is eating away at your wealth compounding over many years.

Below, you’ll see that with the same sequence of returns for an active (yellow line) and passive index fund (red line), higher fees in the active fund will seriously reduce your performance in time . In this example, the difference is almost $100,000 after 30 years where the active fund slightly outperforms the benchmark at 7.2% vs 7% but charges a 0.6% fee.

See You Next Time!

That’s it for today on We Study Markets!

If you enjoyed the newsletter, keep an eye on your inbox for them on weekdays around 12 pm EST, and if you have any feedback or topics you’d like us to discuss, simply respond to this email.

Have a great rest of your day!

P.S The Investor’s Podcast Network is excited to launch a subreddit devoted to our fans in discussing financial markets, stock picks, questions for our hosts, and much more! Join our subreddit r/TheInvestorsPodcast today!