Managing Debt Crises

18 January 2023

Hi, The Investor’s Podcast Network Community!

💴 The yen was all over the place today as the Bank of Japan continues to confound investors: It decided to keep rates unchanged at its latest policy meeting after shocking markets with a shift last month.

The move sent both U.S. Treasury and Japanese Government Bond prices higher as the popular “carry trade” enabling traders to borrow in yen at low rates and earn a higher return buying Treasuries remains alive.

And despite seeing its net income jump 25% last quarter, Charles Schwab (SCHW) stock fell today after missing analyst estimates for adjusted earnings and revenue.

Pittsburgh-based bank PNC Financial Services Group also fell today after a jump in year-over-year earnings that still came in short of expectations (PNC) 👎

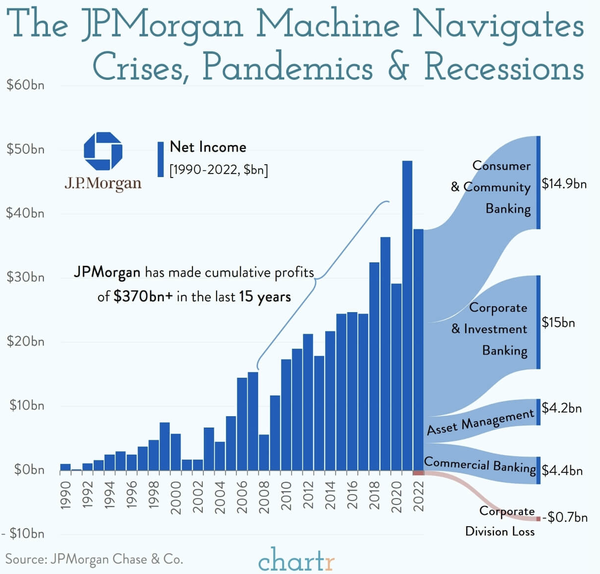

Here’s the market rundown:

MARKETS

*All prices as of market close at 4pm EST

Today, we’ll discuss two items in the news: Last year’s top-performing commodity (hint, it’s not what you think), and how Russia’s economy is adjusting to sanctions, plus our main story on Ray Dalio’s plan for managing debt crises.

All this, and more, in just 5 minutes to read.

Get smarter about valuing businesses in just a few minutes each week.

Get the weekly email that makes understanding intrinsic value

easy and enjoyable, for free.

IN THE NEWS

🍊 Why is Orange Juice so Expensive Right Now? (WSJ)

- It’s a troubling time for citrus fruit lovers, as Florida orange growers are producing their smallest crop in 90 years due to an ill-timed freeze, two hurricanes, and a disease that has laid waste to entire groves.

- Orange production in the Sunshine State is expected to yield less than half of last year’s bounty, marking a 93% decline from peak output in 1998.

- Even worse, the oranges grown are expected to be smaller than usual, meaning more oranges will be needed to produce the same amount of juice.

- The poor harvest is a sharp blow to an industry that’s become synonymous with Florida, with California producing more oranges for the first time since World War II. The shortage has sent futures prices for frozen orange-juice concentrate to record levels after rising 40% last year.

- One commodities analyst called orange juice “liquid gold” after not-from-concentrate juice started selling for over $10 a gallon.

- Long-term prospects for the Florida orange remain bleak as researchers struggle to find remedies for a citrus greening disease spread by Asian citrus psyllids. While America’s preference for orange juice has declined over the years, being seen as too sugary, supply is falling faster than demand, it seems.

- For many young Russians, the war in Ukraine was good reason to leave, with as many as one million doing so. For others, the wave of sanctions cutting the country’s ties with much of the global economy has created new business opportunities.

- After Western brands fled the country, Russians saw Krispy Kreme convert to “Krunchy Dream,” Starbucks to “Stars Coffee,” among others. For two sisters starting a water sports apparel business, one remarked, “We think there’ll be huge demand, and there’s no competition at the moment.”

- Franchise owners are coping with multinationals’ exits by mimicking their products with slightly different packaging. Others are turning to Chinese factories to source goods for their new businesses. Kremlin officials call this the “mobilization economy,” with Russian President Vladimir Putin remarking that they must “give maximum freedom to people who are conducting business.”

- While many have compared Russia’s newfound economic isolation to the Soviet era, it may be more akin to the 1990s, just after the collapse of communism. With huge gaps in supply chains at the time, entrepreneurs and consumers found creative solutions to fill them. This adds inefficiencies, though — It’s estimated that Russia’s economy contracted 2.7% last year and will shrink another 2.5% in 2023.

- Russian officials hope that a wave of entrepreneurship will reinvigorate the economy. Despite an extensive black market developing, sanctions are still inflicting pain. Used cars fetch a substantial premium to what they would cost new, for example.

- It’s not just Russian entrepreneurs capitalizing on opportunities, many Chinese firms have also filled the vacuum. Notably, Xiaomi Corp. dethroned Samsung as Russia’s bestselling smartphone maker last year.

WHAT ELSE WE’RE INTO

📺 WATCH: Bed, Bath and Beyond’s potential bankruptcy, explained

👂 LISTEN: An overview of Aswath Damodaran’s The Little Book of Valuation, on We Study Billionaires

📖 READ: Egg prices exploded higher 60% last year. These foods also jumped

Debt crises and financial panics have transcended time and space, rearing their ugly heads across nearly every major civilization to have ever existed.

As we work through an inflationary crisis while central banks are raising interest rates and pulling money out of the global economy, it seems appropriate to check in with Ray Dalio, author of the excellent book Principles For Navigating Big Debt Crises.

To better understand the big picture of where we are and where we’re going, Dalio tells us that there are five main parts of our “money-credit-debt-markets-economic machine.”

These include:

In this machine, there are a few major players:

- Those who borrow from others and become debtors

- Those that lend to them and become creditors

- Financial intermediaries between the two (aka banks)

- Government-controlled central banks that can create money and credit in a country’s currency and determine the cost of money and credit by raising or lowering interest rates

Piecing it together

Dalio tells us that although goods, services, and investment assets can be bought with either money or credit, only money can “settle” these transactions.

For example, buying a car with all cash provides finality to the deal for both parties, whereas taking out a loan to pay for the car creates a lingering obligation, despite acting like money (by allowing you to take ownership of the car).

“Credit produces buying power that didn’t exist before, without necessarily creating money. It allows borrowers to spend more than they earn…while creating debt that requires the borrowers, who are now debtors, to spend less than they earn when they have to pay back their debts.”

How debts grow

Debt-fueled economic expansions can only occur when creditors are willing to lend, and debtors are willing to borrow, which is captured by the interest rate they mutually agree on. If rates are too high for borrowers, they will have to slash spending or sell assets to service their debts.

This, in part, is why the economy has slowed, and the stock market has declined as the Fed began pushing interest rates up across the economy in 2022.

If rates are too low, lenders will hamper nominal economic growth by refusing to lend, as they don’t feel adequately compensated for the financial risks they’re incurring.

For over a decade, central banks have largely aimed to suppress interest rates to boost credit expansion and economic growth by keeping rates low. To compensate lenders, they ‘printed money’ to buy their debts.

Productive lending

Regular, non-central banks are incentivized to earn profits by lending at rates that exceed their borrowing costs.

This facilitates the flow of capital for society.

So long as these loans are made productively, meaning that borrowers can utilize the funds and then pay back the loans entirely, the system typically works well for all involved.

However, debt crises occur if loans can’t be sufficiently paid back en masse.

Dalio says, “big debt crises come about when the amounts of debt assets and debt liabilities become too large relative to the amount of money in existence and/or the amounts of goods and services in existence.”

In a debt crisis, when debts have become too large compared to society’s incomes and ability to manage said debt burdens, there are four possible solutions:

Managing crisis

Austerity cuts activity across the economy, making everyone “poorer,” which makes it the most painful choice and, therefore, the path least followed historically.

Dalio tells us that the best response to a debt crisis is a “beautiful deleveraging,” where policymakers restructure debts to reduce them or spread them out over longer periods, balanced with central bank money printing that eases debt burdens.

Because central banks can only print money in their own currency (the Fed can’t print euros), beautiful deleveragings are much less likely when most of a country’s borrowings are denominated in a foreign currency or gold/silver.

Takeaways

In summary, Dalio argues that “debt crises are inevitable,” as collective exuberance in good times fuels excess borrowing that makes the bad times worse as sentiment reverses dramatically.

We are likely in the midst of a debt crisis, though so far, policymakers have seemingly threaded the needle on a beautiful deleveraging. This doesn’t mean that in the coming years debt crises can be avoided entirely, but there’s some reason for optimism that these can be mitigated.

Dalio believes that “Most debt crises, even big ones, can be managed well by economic policymakers and can provide investment opportunities for investors if they understand how they work and have good principles for navigating them well.”

Dive deeper

What do you make of Dalio’s blueprint for debt crises?

To read his recent post on the topic, you can find that here. Or check out his full book on Principles For Navigating Big Debt Crises.

That’s it for today on We Study Markets!

See you later!

If you enjoyed the newsletter, keep an eye on your inbox for them on weekdays around 6pm EST, and if you have any feedback or topics you’d like us to discuss, simply respond to this email.