Understand the financial markets

in just a few minutes.

Get the daily email that makes understanding the financial markets

easy and enjoyable, for free.

What Mean Reversion Is, and How to Invest Using It

By Rebecca Hotsko • Published: • 10 min read

Economic booms and busts, or the peaks and troughs of the stock market, are typical examples of ‘mean reversion.’ However, investors often overlook how mean reversion affects companies’ valuations, the broader markets, and some are even trying to understand mean reversion for the first time.

WHAT IS MEAN REVERSION?

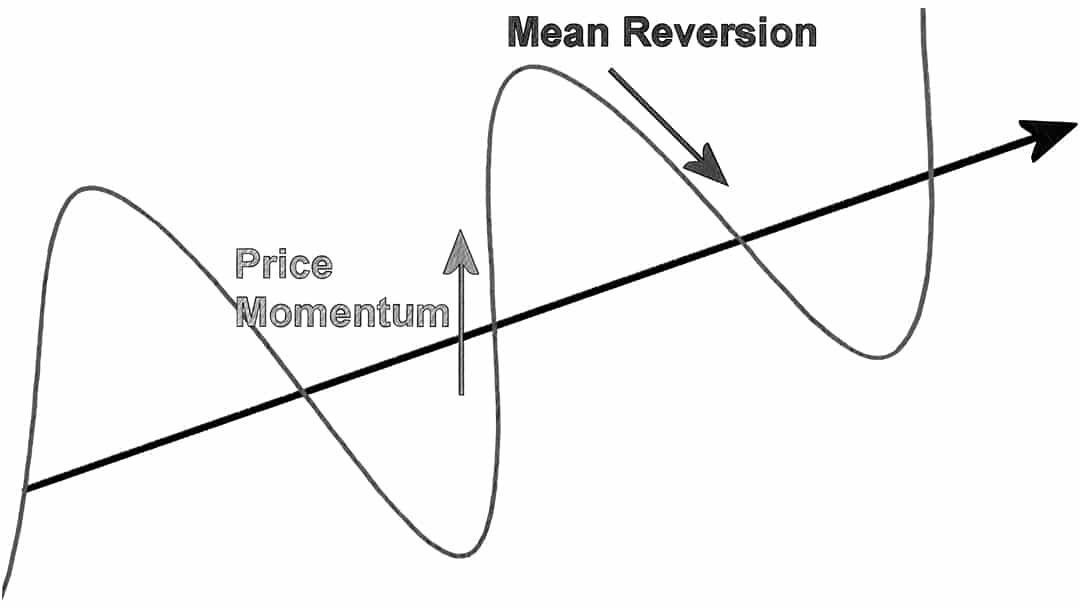

The concept of mean reversion, also known as reversion to the mean, is a prevalent theory in finance that posits that the volatility and past performance of an asset’s price will eventually return to the average level over the entire data set.

Famed value investor Jeremy Grantham argues that “profit margins are probably the most mean-reverting series in finance, and if profit margins don’t mean revert, then something has gone badly wrong with capitalism. If high profits don’t attract competition, there’s something wrong with the system.”

Buffett agrees, and in 1999, he stated, “you must be wildly optimistic to believe profits can remain high for any sustained period.”

WHAT CAUSES MEAN REVERSION?

At an industry level, competition is the primary reason why mean reversion occurs, as fast-growing or highly-profitable industries attract new challengers.

This competition eats away at companies’ growth and profits. Eventually, the once fast-growing, profitable companies lose their competitive advantage or hit a mature point where most of their target market has been tapped.

If you take a step back and think about it simplicistly or logically, it makes perfect sense.

If there is a company that is growing wildly with significant margins, doesn’t it make sense that a company would come in and try to steal some of that market share?

It’s similar to an investor’s required rate of return. You might not buy a stock at a 3% Earnings Yield or a rental property at a 10% cash-on-cash return, but there might be somebody that is willing to. That’s how that stock or rental property can get bought and sold.

With a company’s profits and margins, they might be running at 80% gross margins and be happy with that. A competitor could come in and be happy with 70% gross margins. Because of that, they can likely offer a similar product at a lower price, which is attractive to potential customers.

This is the typical business’s life cycle, and it significantly impacts your returns as an investor.

MEAN REVERSION HAS TWO CRITICAL IMPLICATIONS FOR INVESTORS

Highly-profitable companies growing faster than the average tend to slow down and become less profitable over time.

Companies that were once profitable but now have declining profits, slowing growth, and are cheaply priced, may actually perform better over time.

A simple mistake that investors make is overpaying for fast-growing profits at present by extrapolating that growth unrealistically into the future.

If a company’s earnings per share (EPS) is growing above the market average of about 13% for the S&P 500 on a five-year basis, then the company’s shares should also be worth a premium to the market multiple.

Long-term returns, then, are derived from the company’s earnings growth, share price multiple expansions or contractions (price paid for a dollar of earnings), dividends, and share buybacks.

As investors, it’s essential to make educated guesses on how these factors will drive our returns in the future.

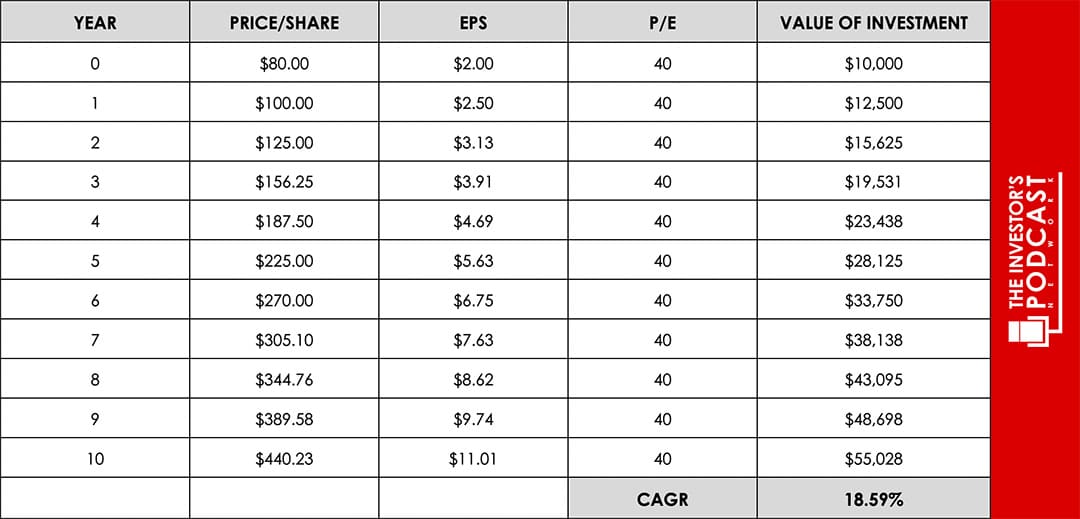

Let’s consider a company that can grow its earnings per share at an exceptional 25% rate.

This impressive growth should warrant that the stock trades at a premium to the market.

While a high-growth firm could outperform for years, most companies can’t sustain such elevated returns before new competitors drive their margins down, as I mentioned before.

Consequently, you might think that a company growing so fast would warrant paying almost any price to own it. However, your return depends not only on the company’s growth rate, but also the multiple, or price, you paid for that growth.

While it’s impossible to predict where a future price multiple will be, history shows that it tends to be very mean reverting.

Let’s further assume that the stock trades at a price-to-earnings ratio (PE) of 30, which is a premium to the average market earnings multiple of 20.

If this company wields 20% growth rates for any meaningful period, it’s less likely, not more likely, that it can continue doing so.

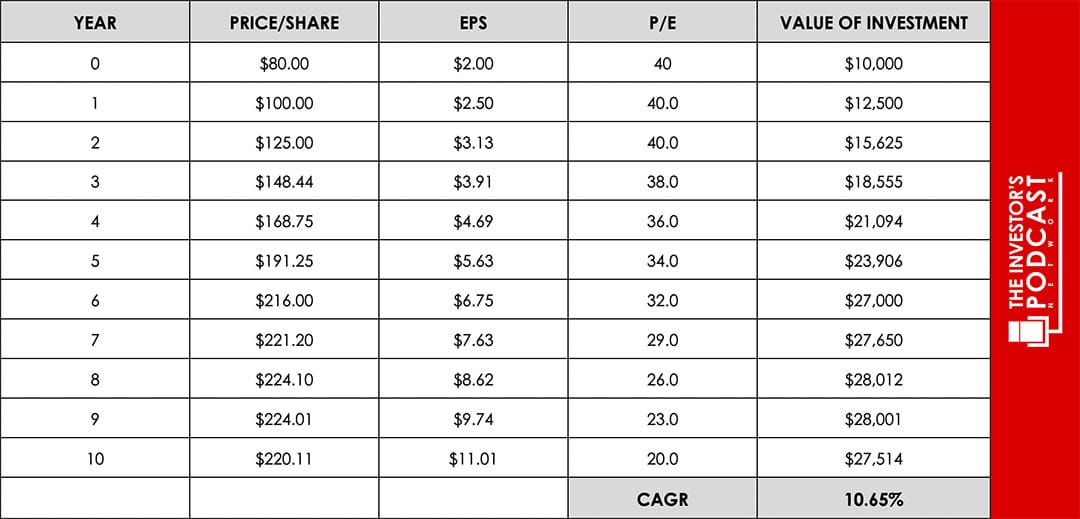

Suppose the company grows at 25% for three years before slowing to 20% in years 3-6 and then plateauing at the market average of 13% in years 6-10.

At the same time, because growth is slowing, the earnings multiple investors are willing to pay contracts from 30 to the market average of 20.

This is the result:

Over time, as growth slows and the price multiple for its share correspondingly contracts, this investment’s compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over ten years is 10.65%, and you would have turned $10,000 into $27,514.

This isn’t bad by any means, but it’s far from the 20-25% rate you might have expected from this high-growth company.

Don’t forget, though, that the higher the multiple you pay today, the bigger deal this is to your return later on.

Let’s compare our results with what an investor would get if the company could maintain the same multiple:

This result is drastically different from the first, where an investor expected this stock to earn an 18.59% CAGR over ten years with overly optimistic future price multiple expectations.

It’s often more reasonable to assume a company’s growth will revert to its industry’s average, as opposed to the market average, and compare those results.

Hopefully, this helps frame how to reconcile forecasts for an investment’s future earning growth with the anticipated earnings price multiple to develop better investment return expectations.

And if you’re stuck or want to know the historical growth rates by sector (compounded annually), along with the five-year growth rates in EPS, Aswath Damodaran publishes these data sets on his website.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT MEAN REVERSION

Understand the financial markets

in just a few minutes.

Get the daily email that makes understanding the financial markets

easy and enjoyable, for free.

About The Author

Rebecca Hotsko

Rebecca Hotsko is an investor and entrepreneur based in Canada. Most recently, she co-founded a luxury boat sharing club in Kelowna B.C. Rebecca graduated from the University of Saskatchewan with a bachelor’s degree in Economics and since has completed CFA level I and II. In prior years, Rebecca gained valuable experience working as an analyst for the Bank of Canada, the federal energy regulator and in investment management. Her passion for teaching others how to invest using time-tested strategies backed by empirical data also led her to create an investing blog in 2020.

Rebecca Hotsko

Rebecca Hotsko is an investor and entrepreneur based in Canada. Most recently, she co-founded a luxury boat sharing club in Kelowna B.C. Rebecca graduated from the University of Saskatchewan with a bachelor’s degree in Economics and since has completed CFA level I and II. In prior years, Rebecca gained valuable experience working as an analyst for the Bank of Canada, the federal energy regulator and in investment management. Her passion for teaching others how to invest using time-tested strategies backed by empirical data also led her to create an investing blog in 2020.